Contact detection

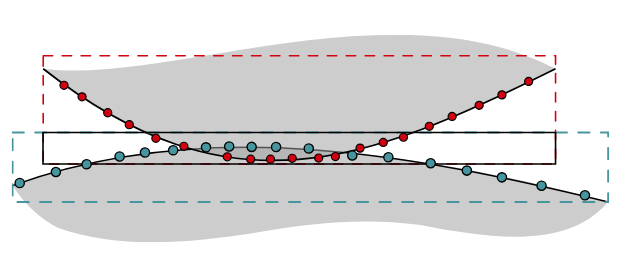

In order to enforce contact constraints, our numerical model must first be able to detect when a part (i.e., a node or element surface) of a discretized body has come into contact with the surface of another body.

As humans, we can visually detect when the violation of contact constraints happens. However, we have to rely on numerical algorithms to make a computer detect such violations. There is a vast body of literature on how to do this efficiently. The overall process can typically be split into two stages:

Broad Phase (Neighbor Search): In a large model, checking every node against every element face (\(O(N^2)\) complexity) is computationally prohibitive. The broad phase uses efficient algorithms (like bounding box trees or spatial hashing) to quickly discard pairs of objects that are too far apart to possibly be in contact, generating a much smaller list of potential contact candidates.

Narrow Phase (Precise Calculation): For each candidate pair from the broad phase, a precise geometric calculation is performed to determine the exact normal gap \(g_n\). For a slave node \(\boldsymbol{r}\) and a master surface, this involves finding the closest point projection \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\) on the surface and calculating \[g_n = (\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}) \cdot \boldsymbol{n}\] where \(\boldsymbol{n}\) is the normal of the master surface at the projection point. If \(g_n \le 0\), a contact constraint is flagged as “active” and needs to be enforced by one of the methods described above.

A Closer Look: The Node-to-Surface (NTS) Contact Detection Algorithm

The general “narrow phase” of contact detection requires a precise geometric calculation to find the gap between potential contact pairs. The Node-to-Surface (NTS) algorithm is one of the most common and intuitive methods to accomplish this.

The core objective of the NTS algorithm is: for each potential contactor node, find the closest point on the opposing surface (the “target” surface). This closest point is the orthogonal projection of the contactor node onto the target surface.

Problem Setup

Let’s consider a single contactor node with current coordinates \(\boldsymbol{r}\). The target surface is discretized into finite elements (e.g., line segments in 2D, or quadrilaterals/triangles in 3D). Let’s focus on a single target element defined by its nodes \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_1, \boldsymbol{\rho}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{\rho}_n\).

Using the standard isoparametric formulation from FEM, any point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\) on this master element can be described as a function of its local (or natural) coordinates \(\boldsymbol{\xi} = (\xi, \eta)\):

\[\boldsymbol{\rho}(\boldsymbol{\xi}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} N_i(\boldsymbol{\xi}) \boldsymbol{\rho}_i\]

where \(N_i(\boldsymbol{\xi})\) are the element’s shape functions. Our goal is to find the specific coordinates \(\boldsymbol{\xi}^* = (\xi^*, \eta^*)\) that define the projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}^*\) closest to \(\boldsymbol{r}\).

The Orthogonality Condition

The closest point is found when the vector connecting the contactor node to its projection, \(\boldsymbol{g} = \boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}(\boldsymbol{\xi})\), is orthogonal (perpendicular) to the target surface at the projection point. This means \(\boldsymbol{r}\) must be orthogonal to all tangent vectors of the surface at that point.

The tangent vectors to the surface can be found by differentiating the position vector \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\) with respect to the natural coordinates: \[\boldsymbol{t}_\xi = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\rho}}{\partial \xi} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \boldsymbol{t}_\eta = \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\rho}}{\partial \eta}\]

The orthogonality condition gives us a system of two nonlinear equations for the two unknown coordinates \((\xi, \eta)\): \[f_1(\xi, \eta) = (\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}(\xi, \eta)) \cdot \boldsymbol{t}_\xi(\xi, \eta) = 0\] \[f_2(\xi, \eta) = (\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}(\xi, \eta)) \cdot \boldsymbol{t}_\eta(\xi, \eta) = 0\]

Solving for the Projection: A Local Newton-Raphson Method

This system of nonlinear equations must be solved iteratively for each potential contact pair at each time step. The Newton-Raphson method is perfectly suited for this local minimization problem.

We can define a residual vector \(\boldsymbol{f} = \begin{Bmatrix} f_1 \\ f_2 \end{Bmatrix}\) and solve for the update \(\Delta\boldsymbol{\xi} = \begin{Bmatrix} \Delta\xi \\ \Delta\eta \end{Bmatrix}\) by iterating:

\[\mathbf{J} \Delta\boldsymbol{\xi} = -\boldsymbol{f}\] where \(\mathbf{J}\) is the Jacobian (tangent) matrix of the residual vector \(\boldsymbol{f}\).

The iterative algorithm for a single slave node and master element is:

Initialize: Make an initial guess for the projection’s natural coordinates, e.g., \(\boldsymbol{\xi}_0 = (0, 0)\) (the center of the element).

Iterate: For \(k=0, 1, 2, \dots\)

- Calculate the residual vector \(\boldsymbol{f}(\boldsymbol{\xi}_k)\).

- Calculate the Jacobian matrix \(\mathbf{J}(\boldsymbol{\xi}_k)\).

- Solve the linear system \(\mathbf{J} \Delta\boldsymbol{\xi} = -\boldsymbol{f}\) for the update \(\Delta\boldsymbol{\xi}\).

- Update the coordinates: \(\boldsymbol{\xi}_{k+1} = \boldsymbol{\xi}_k + \Delta\boldsymbol{\xi}\).

- Check for convergence (e.g., if \(\|\Delta\boldsymbol{\xi}\| < \text{tolerance}\)).

Finalize: The converged coordinates are \(\boldsymbol{\xi}^* = \boldsymbol{\xi}_{k+1}\).

Calculating the Gap

Once the local Newton iteration has converged to the projection coordinates \(\boldsymbol{\xi}^*\), we perform two final steps:

Check Bounds: We verify that the projection lies within the element’s boundaries (e.g., \(-1 \le \xi^* \le 1\) and \(-1 \le \eta^* \le 1\) for a standard quadrilateral element). If it lies outside, the closest point may be on an edge or a vertex, and the algorithm must handle these special cases.

Compute Gap: If the projection is inside the element, we calculate the final geometric quantities:

The projection point on the target surface: \(\boldsymbol{\rho}^* = \boldsymbol{\rho}(\boldsymbol{\xi}^*)\).

The normal vector to the target surface at that point: \(\boldsymbol{n} = \boldsymbol{t}_\xi \times \boldsymbol{t}_\eta / \|\boldsymbol{t}_\xi \times \boldsymbol{t}_\eta\|\).

Finally, the normal gap function: \[g_n = (\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}^*) \cdot \boldsymbol{n}\] If \(g_n \le 0\), contact is considered active and the constraint must be enforced.

Implementing the Node-to-Surface (NTS) Algorithm

The Node-to-Surface (NTS) algorithm is a fundamental technique in contact mechanics. The goal is to calculate the gap between a potential contactor node and the opposing target surface. For this implementation, we will assume the target surface is composed of a collection of linear (straight) finite elements.

The overall process for a single contactor node \(\boldsymbol{r}\) is to find the closest valid orthogonal projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}^*\) among all target segments and then compute the signed normal distance to it. Here are the key mathematical operations you will need to implement.

Calculate the Outward Normal of a Target Segment

For each linear target segment, defined by nodes \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_2\), you need to compute its unit normal vector \(\boldsymbol{n}\).

- Find a tangent vector along the segment: \[\boldsymbol{t} = \boldsymbol{\rho}_2 - \boldsymbol{\rho}_1\]

- Find an orthogonal vector. In 2D, a simple way to get a vector perpendicular to \(\boldsymbol{t} = [t_x, t_y]\) is to swap the components and negate one of them: \[\boldsymbol{n}_{\perp} = [-t_y, t_x]\]

- Normalize the vector to get the unit normal: \[\boldsymbol{n} = \frac{\boldsymbol{n}_{\perp}}{\|\boldsymbol{n}_{\perp}\|}\]

This normal can point in one of two opposite directions. To ensure it consistently points “outward” from the target body, you can use a reference point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_{ref}\) known to be inside the body. The final normal should be oriented to point away from this reference point.

Find the Orthogonal Projection

Next, you need a function that projects the slave node \(\boldsymbol{r}\) onto the infinite line containing a target segment and determines if that projection is within the segment’s bounds.

Calculate the projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\). This point lies on the line passing through \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_2\). It can be found using the following vector projection formula:

- Define the tangent vector: \(\boldsymbol{t} = \boldsymbol{\rho}_2 - \boldsymbol{\rho}_1\)

- Define the vector from the segment’s start to the contactor node: \(\boldsymbol{v} = \boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}_1\)

- The projection point is given by: \[\boldsymbol{\rho} = \boldsymbol{\rho}_1 + \frac{\boldsymbol{v} \cdot \boldsymbol{t}}{\boldsymbol{t} \cdot \boldsymbol{t}} \boldsymbol{t}\]

Check if the projection is “inside” the segment. The projection is only physically relevant if it lies between \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_2\). We can check this by looking at the parametric coordinate of the projection: \[t_\text{param} = \frac{\boldsymbol{v} \cdot \boldsymbol{t}}{\boldsymbol{t} \cdot \boldsymbol{t}}\]

The projection is valid if \(0 \le t_\text{param} \le 1\). Your function should return both the projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}\) and a boolean or integer flag (

inside) indicating if this condition is met.

Find the Closest Valid Point

Now, you will write the main logic that ties everything together for a single slave node \(\boldsymbol{r}\). This involves iterating through all target segments to find the best contact candidate.

- Initialize

min_distance= \(\infty\) andclosest_point_data=None. - Loop through each target segment \(j\) in your surface:

- Use the function from Step 2 to find the projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_{j}\) and determine if it’s

inside. - If the projection is inside:

- Calculate the simple Euclidean distance: \(d_j = \|\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}_{j}\|\).

- Compare and update: If \(d_j <\)

min_distance:- Set

min_distance= \(d_j\). - Store all relevant information for this projection (e.g.,

closest_point_data= {point: \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_{j}\),normal: \(\boldsymbol{n}_j\)}, where \(\boldsymbol{n}_j\) is the normal of segment \(j\) from Step 1.

- Set

- Use the function from Step 2 to find the projection point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}_{j}\) and determine if it’s

- After the loop finishes, the

closest_point_datawill contain the information for the single best projection point.

Calculate the Final Gap

Finally, use the result from the search loop to compute the signed normal gap.

- If

closest_point_dataisNone(meaning no valid projections were found), the node is not in contact, and the gap can be considered inactive (e.g., return a large positive number). - Otherwise, retrieve the closest point \(\boldsymbol{\rho}^*\) and its normal \(\boldsymbol{n}^*\) from

closest_point_data. - The signed normal gap \(g_n\) is the dot product of the vector connecting the points with the normal: \[g_n = (\boldsymbol{r} - \boldsymbol{\rho}^*) \cdot \boldsymbol{n}^*\]

This value \(g_n\) is the final output. If it is negative, it indicates penetration, and its magnitude represents the penetration depth. If it is positive, it represents the separation distance.